Climate Data Gaps: Are Corporates Prepared for Incoming Regulation?

While climate change has been a growing concern for corporates and investors over the past decade, most companies are still unprepared to implement the robust requirements of disclosure frameworks and develop enterprise risk management approaches to integrate complex climate-related considerations.

The next few years will likely see reporting of varying quality. It will not be unusual for companies to regularly reassess their risk models and climate strategy. There is already an inherent volatility in corporate climate data and this transitional period will further emphasize the caution necessary when making decisions based on corporates’ climate disclosures.

Key Takeaways:

- Climate risk disclosure has increased in the past years, yet most corporates are unprepared to integrate complex climate-related considerations in their strategy and disclosures.

- Incoming regulation will require companies to quickly gain an understanding of their risk exposure and develop robust disclosures. This will present a challenge, as currently, most companies’ rarely go beyond reporting Scope 1 & 2 emissions.

- There is a competitive advantage in experience and the sooner corporates start to develop the infrastructure and know-how needed to support a strong climate strategy the better prepared they will be as expectations grow.

Corporate climate disclosure has increased significantly over the past three years, and yet most companies still have a limited understanding of their actual climate risk exposure. Current and incoming regulatory requirements and frameworks call on businesses to disclose their climate risk exposure throughout the value chain and to develop governance and risk-management procedures accordingly. For most, this will be a new exercise, and it will probably take them a few years to develop accurate disclosures that contribute meaningfully to their decision making.

In the U.K., climate-related financial disclosures have become mandatory for listed and large public companies. The draft European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), implementing the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), require comprehensive and detailed climate related metrics. In the U.S., it is likely that the Securities and Exchange Commission will implement Climate Disclosure Requirements, while U.S. federal contractors will be expected to report climate-related data at varying levels of complexity.

The International Sustainability Standards Board is expected to issue Climate Disclosure standards in mid-2023, which, if adopted under national legislation, could come into force as early as 2024. This trend can be seen more broadly, as increased disclosure requirements are expected to come into force across the world.

The specifics of these initiatives vary, but in most instances, they are based on the four pillars introduced by the Task force For Climate Related Disclosures (TCFD): Governance, Strategy, Risk Management and Metrics and Targets. Since the first publication of the TCFD’s recommendations in 2017, the conversation around climate-related disclosure has grown exponentially. While some attention has been paid to the Metrics and Targets pillar, specifically reporting on greenhouse gas emissions, there has been limited progress in the areas of Governance, Strategy, and Risk Management.

As stated in the TCFD 2022 Status Report, only 4% of companies made disclosures that were in line with all 11 requirements and about 40% disclosed in line with five.

Corporate Climate Data

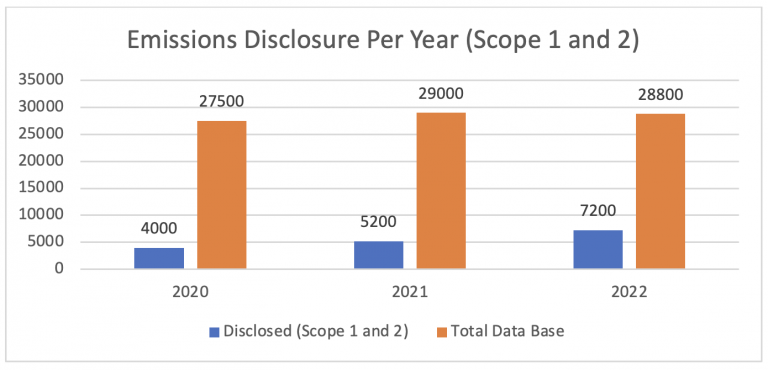

To further illustrate the limited availability and quality of climate data, it can be useful to review the most basic of all climate disclosures: greenhouse gas emissions. For the reporting year 2023, ISS ESG corporate climate database covers the Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions of about 30,000 companies, both reported and estimated.

Since the inception of the database in 2010, both volume and quality have increased significantly. For the latest reporting year, approximately 7,200 companies reported their Scope 1 and 2 emissions. That is a significant increase from 5,600 in 2022. Prior to that, the number had hovered around 3,000-4,000 for several years.

ISS ESG applies a trust metric to all reported data that measures the quality of the reporting and assigns a score from 1 (lowest trust) to 100 (highest trust). Third-party verification is required to get a score higher than 75. For the current reporting year, the average trust metric is 70 and the median 72[1]. About 2,200 companies have externally verified their Scope 1 & 2 data.

Scope 3 is a different story. Despite an increase in disclosures the number of companies reporting is still very low. In addition, the data quality tends to be poor. ISS ESG, the responsible investment arm of Institutional Shareholder Services, discards about 70% of reported Scope 3 numbers, compared with around 1% of the Scope 1 and Scope 2 numbers, primarily due to lack of inclusion of relevant Scope 3 categories. It is also common for companies to change Scope 3 methodologies and recalculate their emissions during the first few years of reporting. Thus, emissions data can change drastically from year to year.

The increase in emissions disclosure is being driven by investor pressure and tighter regulatory requirements. While this is a positive development from a climate risk management perspective, the lack of quality reporting and verification shows that there is significant work to be done for companies to have an adequately granular understanding of their climate risk exposure.

Data Needed to Assess Climate Risk

The underlying driver for regulators and investors calling for this information is a desire for more robust and informed management approaches to protect business value they see as being at risk. It is therefore essential for companies to develop a detailed understanding and disclosure of their risk exposure.

For companies to adequately assess their climate risk exposure they need access to data sets that cover everything from operations, suppliers and commodities to future scenarios. The scenarios should include, for example, carbon budgets, sector trajectories and physical climate risks. This is a complex analysis, and currently few, if any, companies have managed to conduct such an assessment.

The type of information required can be placed into two broad categories: descriptive data and predictive data.

Descriptive data is ex-post data that can be used to assess the current state of a business, i.e., the results of physical activities that have already taken place. For example, location data (corporate and suppliers), energy and material use as well as financial data. The most common use for this type of data is to conduct a greenhouse gas accounting.

The challenges faced by most corporates is how to identify relevant data sources, develop a data collection infrastructure and then interpret the information. For example, it can be surprisingly difficult for an organization to map out detailed material flows.

Predictive data is used for different types of forecasting, for example scenario analysis and assessment of transition and physical risk exposure. This second category is both highly dependent on the quality of the data coming from the first category and the applicability of available predictive models. Most scenarios available and recommended for corporate analysis, for example those from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Network for Greening the Financial System, require significant adjustment and adaptation to provide even moderately actionable inputs on climate risk and strategy.

The descriptive category presents a data problem, as its aim is to give a fair representation of past and current activities. The second category presents a modelling problem, as its aim is to give an indication of potential futures.

To solve the descriptive data problem, corporates need access to two types of tools/resources.

- Tools to collect, sort, and understand data, covering both direct operational information (e.g., electricity consumption), and the broader value chain (e.g., supplier specific activity data). The tools do not have to be climate focused per se, as the problem being solved is a broader data problem rather than a climate specific problem. What is needed is a focused effort from companies to develop an internal infrastructure that supports their overall climate strategy efforts, either by utilizing external expertise or by building internal capacity.

- Tools to assess current climate risk exposure. What this entails will differ from sector to sector, for most, it means calculating GHG emissions throughout the value chain. Compared with the above data collection tools, a more focused climate expertise is generally needed for this type of analysis. However, several public resources are available, for example via national Environmental Protection Agencies.

The more detailed the descriptive data, the better equipped a company will be to make accurate assessments of climate related risk and develop robust management strategies. For example, you will not be able to identify physical and transition risk exposure if you do not know where in the world a company or a supplier operates, where commodities are sourced from, and the resources needed in their production processes. An exhaustive GHG accounting, covering the entire corporate value chain, requires these inputs and provides the foundation needed to conduct a granular risk assessment.

It would therefore benefit many corporates to focus on developing a detailed understanding of their physical footprint during the first few years of their climate risk management journey.

Predictive modelling certainly has a place when constructing a climate strategy, but without relevant inputs the predictions are of limited use.

What to expect from the future?

Incoming regulation will require companies to quickly gain an understanding of their climate risk exposure and develop robust disclosures. This will present a challenge, as currently, most companies’ rarely go beyond reporting Scope 1 & 2 emissions. A benefit of the general corporate inexperience in this field is that all stakeholders, including, corporates, investors and NGOs, have an opportunity to shape the future of climate risk analysis. The regulation can appear to be restrictive, but in this evolving field there is a lot of freedom as to how companies choose to use the metrics developed for the disclosures.

The next few years will likely see reporting of varying quality. It will not be unusual for companies to regularly reassess their risk models and climate strategy. There is already an inherent volatility in corporate climate data and this transitional period will further emphasize the caution necessary when making decisions based on corporates climate disclosures. This can be challenging for investors and other stakeholders who are looking to get a comprehensive view of a company’s climate risk exposure. Corporates themselves also need to take this consideration, for example when setting climate targets, tying executive compensation to climate related metrics or developing a risk management strategy.

A learning curve is to be expected when it comes to such complex assessments, and strategy reassessment should not be a problem if done transparently. There is a competitive advantage in experience and the sooner corporates start to develop the infrastructure and know-how needed to support a strong climate strategy the better prepared they will be as expectations grow.

Notes:

[1] The numbers have been rounded to remove decimals.

California Climate Laws Update: CARB Workshop and SB 261 Pause

California Climate Accountability: Getting Started on SB 253 and SB 261 Reporting

Mandatory Climate Disclosure in South Korea

SEC Adopts Climate Disclosure Rule: Key Takeaways for Corporates

Climate Data Gaps: Are Corporates Prepared for Incoming Regulation?

Latin America’s Sustainability Reporting Gains Momentum

Rare Earth Minerals: The Hidden Backbone of the Energy Transition

Energy Management Systems: Global Trends and Best Practices

2025 Sustainability Reporting: Global Trends in Framework Adoption

Getting Materiality Right: Challenges, Risks, and Best Practices